Updated Bolts Lake design minimizes impact to Minturn by using technology pioneered in Europe

Project engineers lean toward hydraulic asphalt concrete liner to cover highly permeable bedrock as project approaches 30% design

Vail Daily archive

The project to rebuild a bigger, lasting version of the Bolts Lake Reservoir is rapidly taking shape.

Construction on the new reservoir is set to begin in 2029, and it is expected to be ready for use in 2032. The project should be at 30% design by the end of this spring, and field surveying will begin this summer.

The Eagle River Water & Sanitation District and the Upper Eagle Regional Water Authority have been working on building out on the site of the old, long-drained Bolts Lake Reservoir for years to prepare for low water years and climate uncertainty. The district purchased the Bolts Lake property from Battle North in 2022.

The old Bolts Lake had a capacity of around 300 acre feet of water, or enough to cover 300 football fields a foot deep in water. The new reservoir will have a capacity of 1,200 acre feet or higher. The dam will fill during high runoff times in the spring and early summer, then discharge water during drier months in the late summer and fall.

When it comes to building a reservoir, two elements are key: Finding, and then keeping, enough water to fill the space.

Support Local Journalism

At an April 10 joint meeting between the district and authority, engineers from the construction engineering firm AECOM presented options for feeding and lining the reservoir. Craig Helm, with AECOM, is the project’s lead dam engineer.

Cross Creek, Eagle River provide multiple diversion options

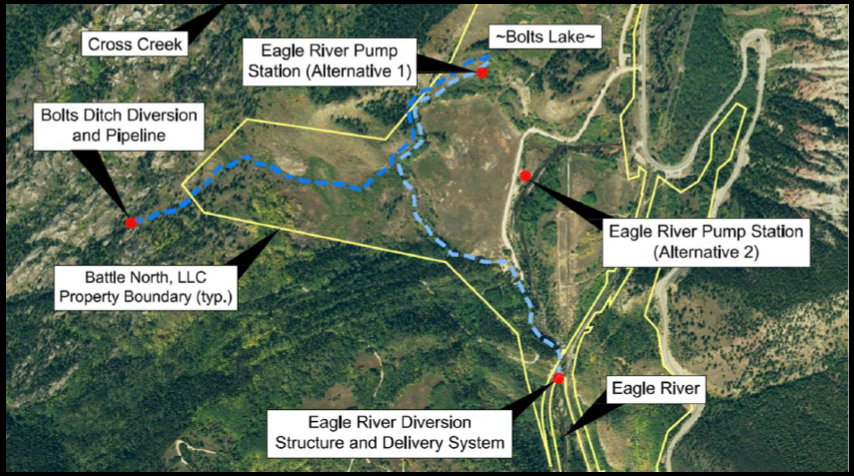

To have a reservoir full of water, the water needs to come from somewhere. The original design was expected to pull water from two sources: Cross Creek and the Eagle River.

Helm and his team looked at four locations on Cross Creek for potential water diversion sites, including the existing Bolts Ditch headgate (with minor tweaks). The hope is to employ a gravity feed from Cross Creek, using the natural downhill flow of water, diverted in a slightly different direction, to fill the reservoir.

Getting water from the Eagle River to the reservoir will be slightly more complicated, requiring a pump station to push the water uphill. Helm’s team looked at two potential pump station locations on the Eagle River — one noted in the original design selection and one slightly downstream from it.

Join the 17,000 readers who get the news from us daily.

Sign up for daily or weekly newsletters at VailDaily.com/newsletter

Geomorphologists at AECOM are looking at historical images of the Eagle River to confirm spots with long-term stability in the river, where the shape of the river does much of the work without the need for intervention.

The diversions will look like large boulders and rocks stacked in the streambed, creating a weir that holds up water in the river to be drawn off toward the reservoir.

Hydraulic asphalt liner leads as the top choice

The rock upon which Bolts Lake Reservoir is built is highly permeable, meaning water moves through it easily. To keep water in the reservoir, it needs a liner to cover the bottom and sides of the reservoir.

“The reason we’re lining this is because the natural geology is really fractured bedrock,” Helm said. “This is so permeable (that) water will flow out, so we had to actually line the whole reservoir.”

The original Bolts Lake Reservoir had no liner. “But it probably lost most of the water,” said Jason Cowles, the district’s director of engineering and water resources. “The early design stuff we did showed that it was so permeable we would probably lose the entire volume of the reservoir within the course of a year.”

Helm presented three options for a liner: A compacted clay liner, a geomembrane liner and a hydraulic asphalt concrete liner.

The compacted clay liner would combine clay salvaged from a borrowing area in Wolcott with other synthetic liner layers to create a 5.5-foot-thick liner. But on top of the potential for the liner cracking as water levels changed and the possible need to find an additional source of clay, the liner had one giant problem: It would require 32,000 truckloads of clay and other materials to travel through Minturn over a period of roughly two to three years.

The geomembrane, a 45-millimeter thick, relatively flexible layer of reinforced polyethylene that is commonly used for reservoirs, is a good backup option, Helm said. With a cover, this liner could last 40 to 50 years.

But the liner of choice for the project is made of hydraulic asphalt concrete. This technology, while on the newer side in the United States, has been common in Europe for lining dams and reservoirs “for a number of years,” Helm said.

The hydraulic asphalt liner consists of two layers of asphalt — a drainage layer and then a dense, 3-foot-thick layer. “It’s very durable, it’s somewhat flexible,” Helm said. “It’s easy to inspect.”

The hydraulic asphalt liner scored the highest against several other types of liners in many categories, including cost effectiveness, precedent, technical suitability, constructability, operation, performance and maintenance of the options.

The liner would require about 7,000 truckloads of material to travel through Minturn over two to three years. The parts of the liner most exposed to UV rays might need to be replaced in 10 to 15 years.

Most challenging, there are no contractors in Colorado that can install this type of liner. The contractor will need to come from Europe. While the technology is similar to other asphalt contractors in Colorado, smoothly installing the liner on the sides on the reservoir requires work by those who have been trained in it.

To secure a competitive field from European contractors, the bid for the installation of this liner needs to be put out a year or two before work is to begin — less of a challenge for a project set to start construction in four years. The large size of the Bolts Lake project will also help with getting contractors’ attention.

Wetland resources, cultural resources, biological surveys completed in the fall

Ben Johnson, leader of the Black and Veatch team that is managing the project, presented on the project’s progress in analyzing its impacts on the environment around the reservoir based on surveys completed in the fall.

Johnson’s team has engaged Colorado Parks and Wildlife, the U.S. Forest Service, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to seek each organization’s feedback on the project’s impacts and permitting needs.

There is “no sign of any threatened, endangered species in or around the area,” Johnson said.

Construction will need to avoid beaver dams in and around the areas. Wetlands around the Eagle River will be impacted and need to be mitigated if the reservoir pumps water from Eagle River. The pump also needs to avoid pulling in fish. “That is an ongoing conversation with Colorado Parks and Wildlife,” Johnson said.

The reservoir construction may impact two sites that could be candidates for the National Register of Historic Places (but are not yet on the list, or even up for being added): The trestle pipe from the Eagle Mine and Bolts Ditch itself.

A section of the trestle pipe will need to be removed to build the reservoir’s embankment, while the majority will stay in place.

The district is currently blocked from doing construction on Bolts Ditch due to a federal mapping error and is pursuing federal legislation to enable the use of the land again.

A long-dormant US immigration registration law is getting stricter enforcement. Here’s who Colorado attorneys say it impacts

A decades-old law requiring immigrants to register with the U.S. federal government is suddenly getting stricter enforcement, and Coloradans have questions about who it impacts and what it means for their travel.